|

"Sticker Movie" beautifully explores the underground network behind those stickers you spot on street signs and lampposts in cities and towns around the world.

Sticker art culture is the "last bastion of anarchy" and even a form of therapy, according to some of the dozens of artists and fans who appear in the Will Deloney-directed documentary. Oh, and mega-famous street artist Shepard Fairey -- of Barack Obama "HOPE" fame -- stars too. Still can't believe I once spotted one of his Andre the Giant slaps out in the wild. See it here. “Sticker Movie" has its theater premiere at the Portland Cinemagic on October 6. I've seen a preview and definitely recommend checking it out.

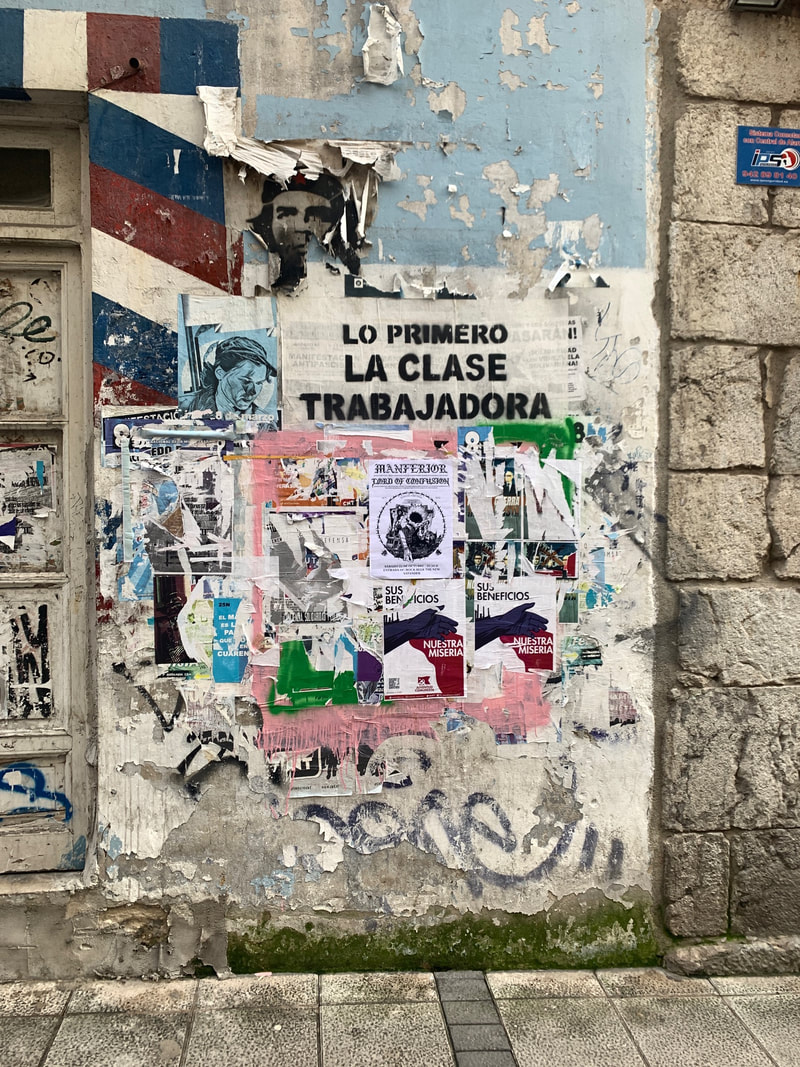

Some photos of the street art (or arte urbano or arte callejero) that I spotted in Santander, northern Spain, in 2022.

For more street art, SIGN UP TO MY NEWSLETTER, FOLLOW ME @ INSTAGRAM & FACEBOOK. I spotted these pieces of street art during a recent trip to Marmande in the Lot-et-Garonne département in south-western France. I'll post more photos of the town itself (famous for its production of tomatoes) in another post and add more street art snaps should I find any more hidden on my camera or phone. Sign up to my newsletter here.

I loved this short, 9-minute film by Doug Gillen -- titled "CHANGE" -- which details the work of the "Void Projects" art collective in Ferizaj, Kosovo.

Some beautiful street art and stories. Per the press release: "Set against the backdrop of a global pandemic, the film follows 10 international artists reflecting on the history of a country healing from war. In collaboration with the local community, this new generation of creatives discover the human stories of Ferizaj. Art in the city becomes a visual celebration of connectedness at a time of shared distance." Artists featured include: Ampparito, Aruallan, Micheal Beitz, Helen Bur, Emilio Cerezo, Doa Oa, Alba Fabre, Ivan Floro, Maria Jose Gallardo, Retry One, Zane Prater, Vlada Trocka and Axel Void Watch the video on Vimeo here:

New film trailered on YouTube by PrismFilms1 on Tuesday.

No release date as of yet. Here’s the description: “The untold story of the world’s most famous artist, the empire he built and the movement he inspired. “The mystery surrounding ‘Banksy’, the anonymous street artist whose illegal stencils, pranks, invasions and interventions have outraged the establishment while captivating ordinary people across the planet for more than two decades. But despite being one of the most important figures of our times, Banksy has remained an enigma, with little known about the circumstances of his life and work. “Banksy & The Rise of Outlaw Art” finally reveals Banksy’s story, from his roots in a criminal subculture to his rise as the leader of an art revolution. “Featuring: art promoter Steve Lazarides; Bristol graffiti pioneer John Nation; renowned street artists Ben Eine, Risk, Felix ‘Flx’ Braun, KET & Scape, plus a host of art experts and cultural commentators.” I covered the Hop Farm Festival in Paddock Wood, Kent, in 2009 and 2010 -- a selection of the stories are below, including an interview with organiser Vince Power:

Dismaland, Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, UK - September 2015. Bants, bantz, banta, banter... whatever you want to call it. I've collected a few banter-related puns below: Banterlope Bantersaurus Rex Banteater Banton Dubec Bantomime Bantlepiece Bantony Hopkins Banterberry tales Bantagonist Banti-christ Bantidote Bantasy Bantastic Bantennae Bantom of the Opera Sweat bants Robantic Archbishop of Banterbury Eric Bantona Throw a Bantrum National Banthem Bantman Forever Jazz Bant Santiago Banterbeau Bantonio Banteras On the Bantlepiece Robantic Bottle of Banta Bank of Bantander SAMANTHA Diplock was a typical nine-year-old girl – full of energy and a real lust for life. But all that changed in May 2008 when she suffered a severe stroke. What followed was every parent’s worst nightmare – six months of intensive care at King’s College Hospital in London, a gruelling 19-hour operation, and another six months of rehabilitation. At first she couldn’t sit up properly, her family describing her as a “rag-doll”. Now she walks, albeit slightly off-balance, and is a shining example to classmates at Hillview School for Girls. As the two-year anniversary of that fateful day approaches, Lee Moran spoke to parents Diana and Nick about what they’ve been through and what the future holds

NICK and Diana Diplock laugh, joke and chat like any other couple – but they’ve just been through two terrible years of pain, anxiety and stress. Their lives were turned upside down in May 2008 when their daughter Samantha, aged just nine, was brought back to life after suffering a near-fatal stroke while at school. “It completely changed our lives. One day we’re an ordinary family and then we’re thrown into chaos,” said Diana. “It’s been unbelievable but we’re coming out of this. We’ve got to be strong for our girl, who’s shown us to go for what we wantt. We can’t be broken people any more.” It was a normal Friday when Diana dropped Samantha off at St Stephen’s Primary School in Tonbridge. But as classes were drawing to a close the bubbly blonde-haired youngster started screaming out in pain, complaining she couldn’t see, before passing out. Amidst the chaos and panic, Melanie Eager, a teaching assistant with a basic knowledge of first aid, sprang into action, carrying her into the school’s music room where she successfully resuscitated her. Samantha was rushed to Kent and Sussex Hospital in Tunbridge Wells where an initial scan revealed she’d suffered a severe brain haemorrhage. Doctors ordered her to be transferred to King’s College Hospital in London to be stabilised. The rapid response team has since admitted it didn’t think Samantha would make it alive to London, where she was “lost” and brought back to life several times on the operating table, before spending two weeks in a coma. “We were told to expect the worst. We just didn’t know what to do. It was a horrible time, we felt so helpless. She eventually started to wake up but her body movement was very slow, she was like a rag doll,” said Diana. The haemorrhage, which doctors said would probably happen again if she did not have corrective surgery, was caused by a rare malformation of the arteries in her brain. Samantha found it difficult to speak, impossible to eat, and was fitted with a tracheostomy so she could breathe through a hole in her windpipe. She made steady progress but the rogue arteries remained, leading her parents to give the go-ahead for a further, risky, 19-hour operation in August 2008, which thankfully proved a success. Two months later she transferred to the specialist Children’s Trust in Tadworth, Surrey, for six months of brain injury rehabilitation and after making outstanding progress she came home in May 2009 to resume lessons at Hillview School for Girls. “The school has been brilliant, we can’t knock them. They’ve done everything to help, she has her own teaching assistant, and her friends have been great in treating her normally. She can’t eat in the canteen as she’s still fed through tubes in her stomach because the muscles in her throat aren’t strong enough. But friends go with her to a room, play on the Wii, and if she was annoyed she’d let us know, and as she doesn’t moan about school they must be doing a good job.” Asked when Samantha, who has two older sisters, would be able to eat properly again, Diana said: “That’s the big question. We don’t know whether it will sort itself out as she gets older. She might need medical intervention. There’s a procedure out there but it’s not been approved in Britain so we’ll have to wait and see.” Diana, who gave up work two years before the incident and now works full-time as her daughter’s carer, said Samantha was still slightly off-balance when walking and needed a wheelchair when tired. “But she’ll keep on going until the last, she’s very strong-willed. “This has made her very determined. She lost a year and I think she wants it back.” Melanie Eager, who saved Samantha’s life, was hardly known by the Diplocks before the tragic events – now she is seen as part of the family. “She saved her life and if it wasn’t for her she wouldn’t be here. Mel’s really been amazing. Samantha doesn’t know everything that happened that day and just thinks of her as a friend. They go off and have fun days together and they get on really well. “One day she’ll know what she did for her but it’s too much for her to understand at the moment.” Nick remained fairly quiet during the interview, happy for his wife to take the lead. But the subject which fired him up was the lack of services available to Samantha in West Kent since they left the Children’s Trust. “We have to fight a lot. We leave here, where we’re almost too well looked after, and once we’re home, bang, we’re on our own,” he said. “It doesn’t matter who takes up our case, there’s always an excuse as to why she can’t have a play therapist, which is essential in helping her progress. We nearly had one but she had to go on unexpected leave so we’re back at square one. We also don’t have anyone to reassure us and offer support. We’d love to speak to people who have been in the same situation.” As our time in the immaculate canteen at the Children’s Trust drew to a close, I asked what the future held for Samantha, who’d been busy packing goodie bags for the charity’s London Marathon runners while we talked. “She goes through phases and I think she’s still too young to know exactly what she wants to do. At the moment she wants to work in a supermarket, but only part- time,” Diana said. “She’s looking forward to helping out at the new Children’s Trust charity shop in Tonbridge. They’ve said she’ll sort the toys coming in, which she’ll love, but she’ll probably want to keep some of the ones she likes." “I JUST want to die,” slurred the man who’d popped a cocktail of pills and was sitting, wild-eyed and agitated, on a sofa in his lounge. His brother, absent-mindedly playing video games, perched quietly as an emergency co-responder went through his sibling’s medication box, finding out what tablets he’d washed down with a bottle of Diet Coke.

“How many of this one, and this one, and this one?” he quietly asked the bleary-eyed and confused patient, surrounded by a filth-strewn room littered with cigarette ends and magazines. I’d just walked into the second floor flat and stood there in disbelief, rooted to the spot, my heart pounding and emotions all over the place. I was following two West Kent paramedics on a Sunday nightshift – and the evening had suddenly become awfully real. As a journalist I’m used to writing and investigating these stories retrospectively. We get told about an incident and we sniff out what happened. But here I was experiencing the story first-hand. It’s what Nick Seddon and Stuart Jordan deal with on a daily basis – and I didn’t particularly like it. Don’t get me wrong, the thrill of racing up London Road to that first overdose call in Sevenoaks was exhilarating. Turning out of Kent and Sussex Hospital’s ambulance station, I gripped the handrail as the speedometer inched its way well over 55mph. As our sirens blared and blue lights blazed, cars parted, showing us a courtesy I’ve never seen since moving to the South East. “I could get used to this,” I shouted over the cacophony of noise as the speed camera by the Hand and Sceptre pub flashed us on our way. We didn’t know what the job involved, only that a man in his 30s was in trouble and someone was already on the scene. I wasn’t sure what to expect – so to walk in on someone who’d just swallowed 200 tablets was a serious shock to my system. Regaining composure I watched as the paramedics made sure he was stable before taking him to the ambulance foramore detailed check-up. “You’ve got the blood pressure of an athlete,” joked Stuart, putting him at ease, before saying he’d have to go to Farnborough’s Princess Royal University Hospital for treatment. Waiting for a nurse, the patient pointed to where a handcuffed teenager wearing an England football shirt sat, monitored by Met Police officers, with his eyes rolled back into his head. “You should interview him for your story,” he laughed. His laissez-faire attitude about what he’d done shocked me – but I later found out he was a “serial overdoser”, as the paramedics called him, who’d done the same a fortnight before. This was a way of life to him and it seemed he liked it. Waiting for the next job to come in, I asked if overdoses were common. “Oh yes, Tunbridge Wells has a big heroin problem. It’s bad on some of the estates, like Showfields, Sherwood and Ramslye, but it happens all over the town,” said Nick. “Tonbridge has it too, but I wouldn’t say the estates there are worse than those in Tunbridge Wells. We have a lot of serial overdosers in both.” A beep sounded, cutting him off mid-sentence, and it was on to a plush modern country house in Underriver, where a an elderly man had collapsed with chronic back pain. He’d been unwell and had suddenly gone downhill, something which Nick and his six years’ experience soon realised could be a kidney infection. Before long we were on our way back up to Farnborough. Astounded by the frenetic pace, I wanted to know whether it’d be busy for the rest of the night, and most importantly, when I could tuck into my sandwiches. “It’s normally pretty non-stop until around 3am, then we’ll have a lull, and at 6am older people wake up and fall out of their beds,” said former personal trainer Nick. Our first three hours had been pretty intense, so what was it like when he first started? Was it an eye-opener? “Yes, definitely. On my first proper night I dealt with a fatal stabbing in Canterbury, the second shift I delivered a baby and on my way to the third there was a crash in front of me so I helped with that too.” Having dropped off our second patient we were called to a serious two-car crash on Seven Mile Lane in East Peckham. Just as I was registering the fact I could be seeing a fatality, we were stood down. We were too far away and, although we’d have made it within the target time, a crew closer to the incident had declared themselves available and were ordered out instead. The system, controlled from central HQ in Coxheath, prioritises incidents and allocates them to the nearest available teams. On the way to a job they can be diverted elsewhere, but once they’ve signed in to a particular location they remain undisturbed, allowed to focus fully on the task in hand. It also means the crews could end up anywhere in the recentlymerged counties covered by South East Coast Ambulance Service – Kent, Surrey and Sussex. This is something the new Make Ready depot system, which has already been introduced into Stuart’s home town of Hastings, will capitalise on. “I love it. It takes pressure off crews as we can pick up clean and fully stocked ambulances and go,” said Stuart, who has one year’s experience and does overtime out of the seaside resort. I desperately wanted the next call to be local and, sure enough, the control room’s super-computer kicked in and we were in Hildenborough, where an 81-year-old had fallen from his wheelchair, smashed his nose on the floor and broken his upper arm. The paramedics, helped by a staff responder already there, worked quickly, methodically and calmly to pump him full of morphine, splint his arm in vacuum-packed polystyrene balls, and lift him into the ambulance. Safely deposited at Kent and Sussex Hospital, we were allowed a short “lunch break“, ironic when it was around 2am, where, joined by the other Tunbridge Wells crew who’d dealt with two men smashing their hands through windows, we swapped stories over food. Nick took a couple of bites of his sandwich and the inevitable happened – a woman on the nearby Showfields estate had serious chest pains. We hopped back into the ambulance and careered down the now deserted streets. The 61-year-old was hauled out on a wheelchair for an ECG scan and taken to Kent and Sussex with suspected angina. Back at the station we were finally given an uninterrupted 30 minutes, but I couldn’t relax knowing that the radio could burst into life at any second. It had now gone 3am the lull started to kick in and we waited... and waited... and waited. The crew, on shift until 7am, were later called to Sevenoaks for standby, but as my eyes were half closed I called it a day and made my weary way home. Trudging through the streets of Tunbridge Wells I reflected on a hectic evening and an incident when a patient’s friend hugged and thanked me for my work. Acutely embarrassed, I quickly explained I was just a journalist and all the praise, and more, should go to the people decked out in green. Interested in my take on what I’d seen so far, she asked me how I’d sum up their work. “Just amazing,” I replied. And I really meant it. YOU might remember Bryony Shaw from Beijing as the Olympian who hit the headlines for swearing on live television.

The windsurfer made the gaffe when asked by the BBC how she felt after clinching bronze in a dramatic race in Qingdao. “I’m quite an emotional and passionate person, and although I cringe in hindsight, it does pretty much sum up how I felt at that time,” she said between laughs at Bewl Water this week. “It would be a dream come true if I got the gold in London but I promise I’ll try and hold back on the expletives.” I met Bryony, a new resident of Tunbridge Wells, by the reservoir for a spot of one-to-one tuition. “I’m really sorry but there’s absolutely no wind at the moment,” she immediately apologised. “We’ll hold back a bit, have a chat, then we’ll get you on the simulator and once the weather changes we can go out for a play.” I was secretly hoping the weather wouldn’t turn as I was terrified of being snapped in a wetsuit by our sadistic photographer. Decked out in a sponsor-laden white T-shirt, blue jeans and shades, the tanned 27-year-old, the first British woman to win an Olympic medal in the sport, spoke about the town she now calls home. “My boyfriend Greg grew up in Horsmonden, so Tunbridge Wells is his local town and he didn’t really have to convince me,” she said. “It’s close to the coast and to airports for when I travel, and it’s nice to have a little getaway away from sport. It’s got great restaurants and shops and we eat out at places like Sankeys and Woods. When we found a nice Edwardian flat I was completely sold on the place.” When not abroad, Bryony is based in Weymouth, where her parents live and where the London 2012 regattas will take place. Her punishing training regime involves lots of weights, cycling, rowing, and as much time out on the water as possible to ensure she can cope with any weather condition which is thrown at her. “We’re a bit like heptathletes," she said. "When the wind’s light you have to be strong and explosive to pump the equipment. The water can also be choppy, wavy or flat. Jessica Ennis has to be powerful for the shot put but also able to run. She has her weaker events and I’ll have my weaker conditions, but it’s all about playing to the strengths. Weymouth can have varied conditions so I have to be fully prepared.” Speaking of wind, we still didn’t have any, and our photographer was getting restless. Was utter calm out on the water a common problem? “England is pretty good for its weather," she replied. “Generally we’ll have weather systems coming through and there’ll be something going on. Sometimes you just have to wait for it to come in. We race over a week in a regatta, and you need a minimum of four races, so you’d hope to do that in that time.” Light wind was also a problem in Beijing, where Bryony was inspired by a Princess Anne pep-talk over supper after disqualification in one race, for a pre- mature start, left her in sixth position. “My medal chances were look- ing slim but the Princess was visiting and my Olympic manager asked my coach whether I’d want to have dinner with her. “They thought it’d be a good distraction for me, rather than turning things over in my head all night. She asked me how it was going and, although she’s a Princess, she brought me back down to earth. She made me realise I was in a special situation, I should enjoy it and I had a chance to medal. It was an awesome team de- cision from my manager and coach. They knew me well enough that it would help me and from that day on I didn’t trip up at all. It was quite a turning point.” What about her prospects on home soil in just over two years’ time? “I’m ranked number one in the world, and I’ve medalled at three World Cup events so far this year. Hopefully the home advantage will play in my favour.” As she pondered glory and all that it entails, the wind picked up and we wandered over to the sim-ulator, a board on a low metal tripod, for a demonstration. Wetsuit donned, and our photographer happy with the series of degrading photos of me in said garment, we dived into the water for a lesson. Struggling to balance and catch the wind, my confidence gradually grew and before long I was surfing to the opposite side of the reservoir. “You’re very good, that’s a tippy board you’ve got. We normally start people up on more stable ones,” shouted Bryony from the motorboat. But it wasn’t easy – the series of movements needed to haul yourself up on to the board is instantly forgettable when you’re getting tired. And as soon as I tried turning the board around I’d plunge headfirst back into the water. The 45-minute lesson left me with a clutch of aching muscles I never knew I had and a new found respect for the professional wind- surfers who dedicate their lives to the gruelling sport. Back on dry land, I asked what the future held, beyond competing for her country. “2012 is the main goal. Depending on how I perform there, then I could definitely do Brazil 2016 as well. After that, who knows?" she replied. “There are whispers of me being involved in sport TV presenting, which I would love to do, and potentially I’d like to be a mother and do that sort of thing. But I’d still want to be involved in sport. I’ll always want to be involved in sport." |

Lee MoranJournalist at HuffPost U.S. -- I'm gradually uploading my archive of photographs of street art (and other things) to this blog. CATEGORIES

All

Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed